Imagine learning you were not the age you thought you were. That, in fact, you were four—or maybe even five—years younger. How would it make you feel? Elated? Buoyed by newfound youthfulness? Or confused and somewhat unsettled as to just how this could be—how you had managed to live much of your life thinking you were several years older?

John Robert “Bob” Moorefield, Keeper at Point San Luis when the Coast Guard took over responsibility for the nation’s aids to navigation, was born in December 1891. Or so he thought. Why he understood 1891 to be his birth year is not known. He joined the Army in 1913. He registered for the draft in 1918. He applied to be a lighthouse keeper in 1925. Neither the Army, nor the War Department, nor the Lighthouse Service ever asked Moorefield to prove his age.

Moorefield served with the Army in the Philippines as a private with the engineer corps and in California with the quartermaster corps at Fort McDowell. After his discharge in 1920, he married and settled in San Francisco. Just before applying for a keeper job, he was an assistant engineer at San Francisco’s Steinhart Aquarium.

Moorefield started his lighthouse service career in April 1925 as second assistant keeper at the Alcatraz Island light. A year later, in April 1926, he was transferred to Point San Luis. At the time of his transfer, the head Keeper was George Watters, the first assistant Antonio Silva.

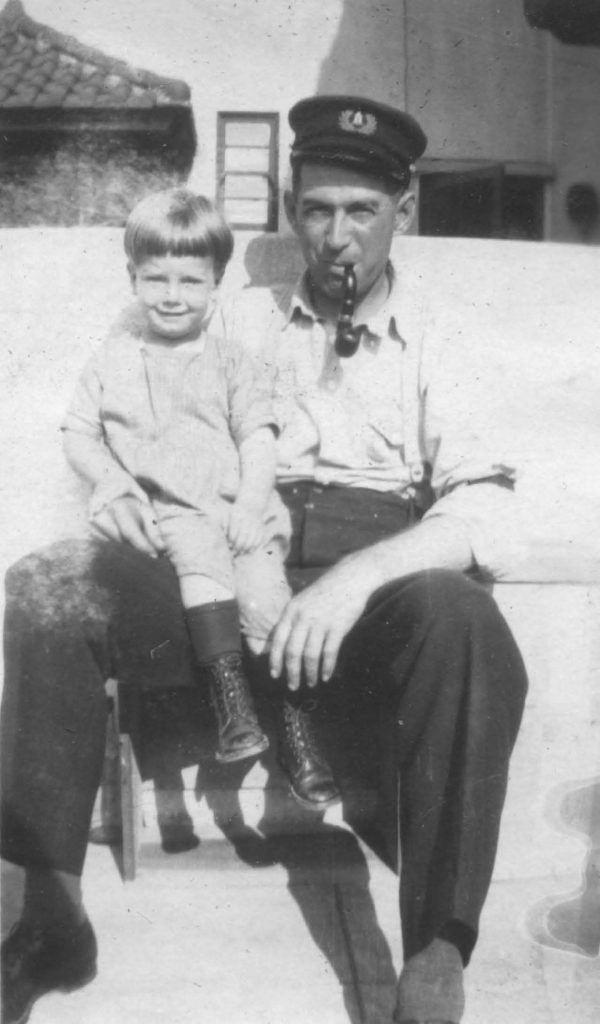

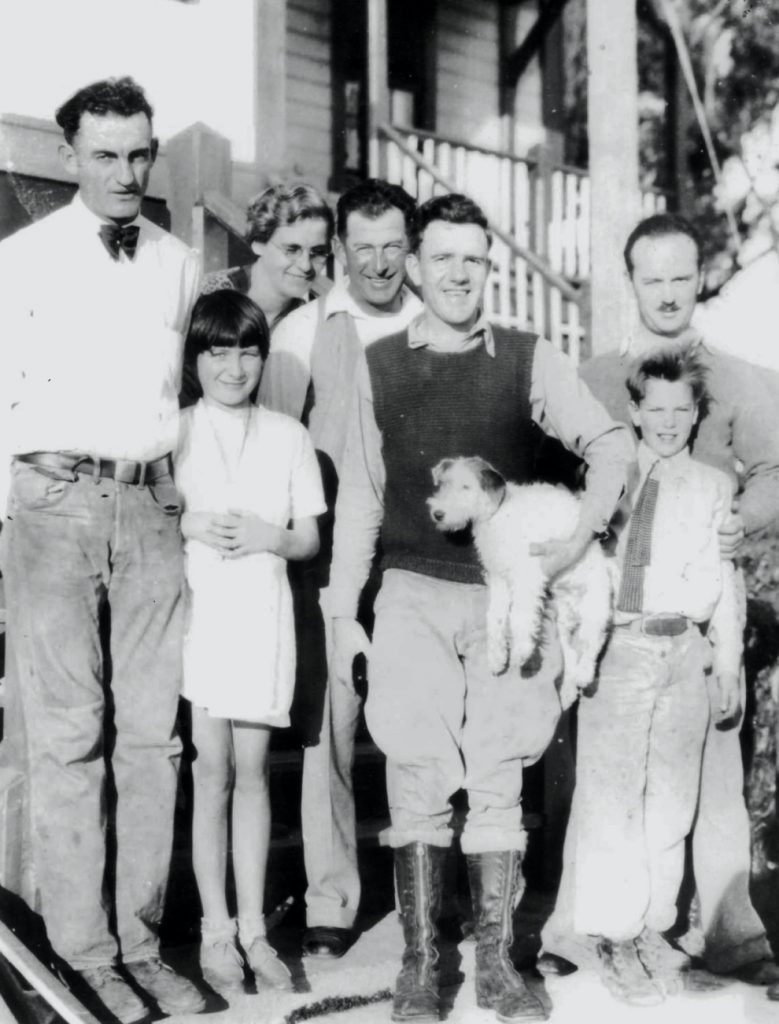

Moorefield divorced his wife in 1928, receiving custody of John Robert Moorefield, Jr., nicknamed “Sonny,” their five-year-old son. In 1929, Moorefield married Mary Elizabeth Studle and became stepfather to Lucy, her seven-year-old daughter.

In 1933, Moorefield was promoted to first assistant keeper when Antonio Silva retired. The Keeper then was Fred Saunders, who replaced Watters in 1929. In 1936, Moorefield was promoted to head Keeper when Saunders transferred to Carquinez Strait. In 1939, shortly after President Roosevelt’s Reorganization Order #11 consolidated the Lighthouse Service with the Coast Guard, his daughter Judith was born.

Top right, Circa 1925 photo of Bob Moorefield and his son John Robert “Sonny” Moorefield, Jr. taken at the Alcatraz light station. Photo courtesy of the Point San Luis Light Station archives.

Bottom, Circa 1932 photo of Bob Moorefield, fourth from left, his wife Mary Elizabeth, third from left, his stepdaughter Lucy, second from left, and his son “Sonny” held at the shoulder by an unidentified man. The man on the left is Mrs. Moorefield’s brother Ted Studle; the man holding the dog is family friend Albert Proteau. Photo courtesy of Curt Brohard

It wasn’t until 1940, as he was approaching his forty-ninth birthday that his age came into question.

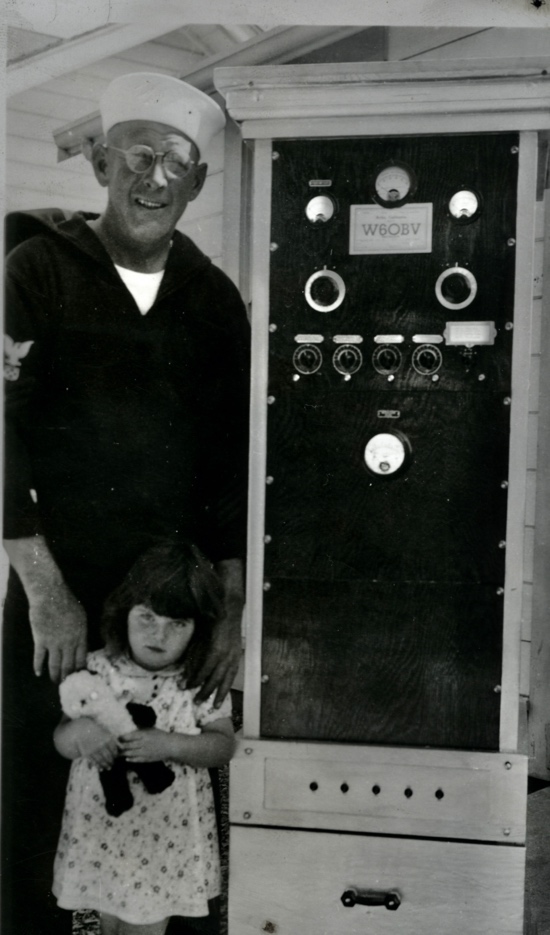

An ardent ham radio enthusiast, Moorefield operated a low-powered amateur radio station, W6OBV, at the lighthouse in his spare time, having converted the station’s coal shed—no longer needed—into a radio room. In June 1940, ten months after World War II broke out in Europe; the Federal Communications Commission issued a ruling requiring all radio operator license-holders—amateur as well as commercial—to prove their United States citizenship.

Moorefield didn’t have a birth certificate, so he wrote to the Registrar of Vital Statistics in Virginia, the state where he was born, to obtain a copy of the registration of his birth. What he got surprised him. On Aug. 4, 1940, he wrote to his Coast Guard superiors:

I have obtained a copy of the registration of my birth from the State Registrar at Richmond, Virginia. And have discovered that I was born Dec. 6, 1896, and not Dec. 6, 1891, as all previous records show. I do not know when the mix-up in my age occurred; for more than thirty years, I have been under the impression that I was born in 1891…The certificate of registration of birth has been forwarded to the F.C.C. in compliance with the Commission order…

If Moorefield thought that would put an end to the matter, he sorely underestimated the government’s tenacity.

The Coast Guard fired back:

Proof of the date of your birth must be established in accordance with inclosures [sic] (1) and (2). If you can obtain a copy of your birth certificate, this must be furnished. You are directed to comply with instructions contained in the inclosures [sic] at the earliest practicable date.

What the two “inclosures” were is not known, but one of them was most likely Civil Service Commission Form 2473.

Moorefield replied:

My birth certificate was sent to the Federal Communications Commission…about Aug. 5, 1940. As soon as it is returned to me, it will be forwarded to the District Office.

I had a photostatic copy of the certificate made but did not receive it in time to have it notarized before the original was sent to Washington; the copy is inclosed [sic] as it may be acceptable and a possible delay be avoided as I do not know how long the Federal Communications Commission will hold the original.

Could the government accept the photostat copy? The Coast Guard asked the Civil Service Commission, only to be told:

In view of the fact that this certificate was not filed with the Registrar of Vital Statistics at or near the time of the birth of Mr. Moorefield, it is not acceptable proof…The data for this certificate appears to have been taken from a family Bible record which, if it meets the requirements outlined under paragraph 3 of Form 2473, may be considered as proof of his date of birth. It will be necessary, therefore, for Mr. Moorefield to submit either the original record or a photostat copy of it to this office, being certain that the date of publication of the Bible is included, in the event that he is not able to furnish a Baptismal Certificate which is a preferred form of proof.

Moorefield obtained the family Bible and sent it to the Coast Guard, but the Civil Service Commission rejected this evidence stating:

The family Bible record was not acceptable because date of birth entered several years after the birth occurred. The record from his grandfather’s Bible clearly indicates that the date of birth was changed from 1895 to 1896.

Paragraph four of Form 2473 allowed a statement of a practicing physician certifying that he attended the birth to be given as evidence, but an affidavit from Moorefield’s sister stated that the doctor who attended the birth and the minister who baptized Moorefield were both deceased. Therefore, the Civil Service Commission concluded none of the forms of proof listed under Form 2473’s paragraphs one through four were available. The last resort was to rely on Form 2473’s paragraph five, and Moorefield was asked to sign a release and fill out a form authorizing the Civil Service Commission to obtain his census records.

But the release hit a snag. Moorefield had only a general idea about where he lived on Jun. 1, 1900, the first census taken after his birth. He wrote:

I have made every effort to establish the correct address of my parents as of Jun. 1, 1900, but I have been unable to locate the exact address with certainty. As near as I have been able to determine, my father lived on a farm near Abingdon, Va. The owner of the farm was probably Milton Moore.

Fortunately, this explanation appeared to satisfy the Census Bureau, and his 1900 census record was located. The government determined his date of birth to be Dec. 6, 1895:

Enumeration in the Census of 1900 of John R. Moorefield, age 4, month and year of birth given as December 1895, the 6th day claimed by appointee, accepted in the absence of the more preferred forms of proof.

Moorefield was advised of his new date of birth on Jan. 30, 1941, when he officially became forty-five years old instead of forty-nine, turning four years younger.

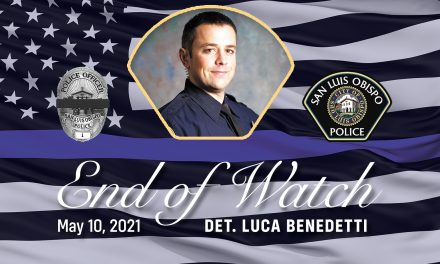

Having now an official age, the path was cleared for Moorefield to join the Coast Guard. He resigned as Keeper, Point San Luis, on Jul. 6, 1941, and enlisted in the Coast Guard the next day.

Now a boatswain’s mate first class, Moorefield continued to serve as Keeper at Point San Luis until his retirement on Feb. 1, 1947, at the (new, younger) age of fifty-one.

A version of this story first appeared in the March–April 2018 edition of Lighthouse Digest magazine.