Commended and Reprimanded

When Henry Young, Point San Luis’ first head Keeper, transferred to the Alcatraz light in 1905, William Smith replaced him. It was a promotion for Smith, who had spent the previous 11 years—except for a short stint at the Farallon Island lighthouse—as an assistant keeper at Point Arena.

Smith’s service at Point San Luis was marked by loss, commendations, and criticism. He lost a wife, a daughter, and his health. He received recognition for how well he managed the light station but also a reprimand for harshly treating his two assistants.

Smith was born in 1861. His family lived on a farm in Wisconsin until 1872 when they migrated to Chehalis County, Washington Territory. There, on 120 acres near the town of Satsop, Smith’s father farmed raised livestock, and operated a dairy.

In 1883, Smith married Nancy “Nannie” Lane in Chehalis. How and where they met is unknown.

The Smiths had four children: Elsie, Bessie, Edna, and Ralph, born between 1884 and 1890. They must have moved around a bit. Elsie was born in Oregon; the rest of the children were born in California—Bessie, and Edna in Mendocino, Ralph in Fresno.

In August 1894, district inspector Henry Nichols nominated Smith for a lightkeeper post; history does not record why. Smith’s own words do not help to explain. Asked about his qualifications, Smith wrote that he was “qualified by the habit of attending strictly to whatever duties I may have on hand, leading a temperate life.” He was assigned to Point Arena as third assistant keeper; promoted to second assistant in 1896.

Smith was transferred to the Farallons and promoted to first assistant in January 1901. Ten months later, he was transferred back to Point Arena. In November 1905, Smith was transferred again, assigned to Point San Luis, and promoted to Keeper.

Six months after his transfer, Nannie died. The care of their offspring now fell solely to the Keeper, although no doubt Elsie, 22 years old when her mother passed away, helped keep house. It must have been a difficult time.

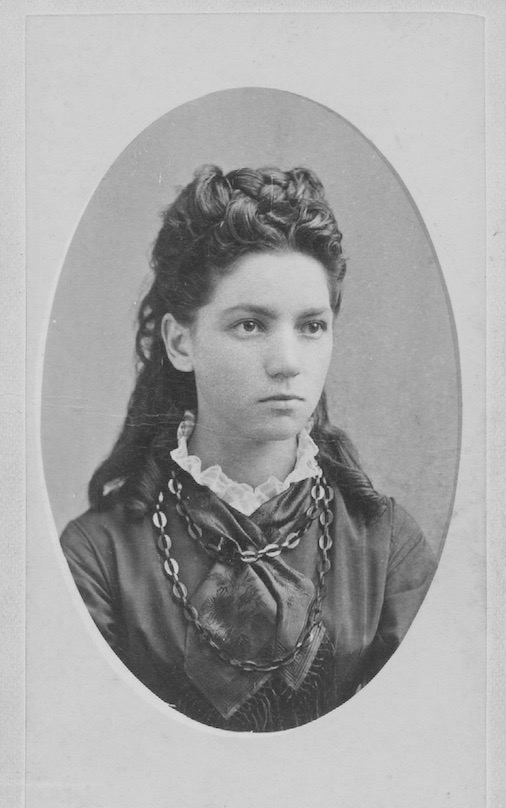

Left, undated photo of Nancy “Nannie” Lane Smith. Center, undated photo of (left to right) Elsie, Edna, and Bessie Smith. Right, undated photo of William Smith. Photos courtesy of Marjorie Fox, his great-granddaughter

Three years later, Smith remarried. The courtship was short. In August 1909, a local paper reported Mrs. Julia Gardner was visiting “El Pizmo” from Illinois. On September 5, she visited the lighthouse. On October 1, Smith married Mrs. Gardner, a “popular lady,” according to the local press, with “many friends in San Luis Obispo.”

Smith’s children were popular, too, it seems, with the local papers often noting their comings and goings. Bessie, Edna, and Ralph attended San Luis High. Bessie and Edna graduated in 1908, then attended the State Normal School in San Jose to obtain their teaching credentials. Ralph graduated from San Luis High in 1911, then went to UC-Berkeley to study dentistry.

By 1911, Edna had finished her studies and was teaching in Rucker, near Gilroy. By 1912, Bessie, too, had graduated and was teaching in Cayucos.

In 1912, to promote “efficiency and friendly rivalry among lighthouse keepers,” the Bureau of Lighthouses introduced a system of efficiency stars and pennants as rewards for good lighthouse management:

Keepers who have been commended for efficiency at each quarterly inspection during the year are entitled to wear the inspector’s star for the next year…The efficiency pennant, being the regular lighthouse pennant, is awarded to the station in each district, showing the highest efficiency for a year and may be flown during the succeeding year.

Smith was commended for efficiency at each quarterly inspection that year and so was awarded the inspector’s star.

Smith’s daughter Elsie married Alfred Howard in August 1913. That same month Smith was awarded the efficiency pennant. Sharing in that distinction were the two assistant keepers, Antonio Silva and Bernard Linne. The district inspector, now Harry Willet Rhodes, wrote:

The inspector takes pleasure in notifying you that your station has been awarded the efficiency pennant of this district, based on the marks for general efficiency given during fiscal year 1913 and that you are entitled to fly this pennant in the manner described by the regulations during fiscal year 1914.

Rhodes also wrote:

As you have been entitled to commendation for efficiency at each inspection of your station during the past year, you are authorized to retain the efficiency star awarded to you at the close of fiscal year 1912. In re-awarding you the efficiency star, the inspector again commends you for the efficient and conscientious manner in which you have discharged your duties during the year.

Even though the girls no longer lived at the light station, they still came to visit. Elsie Smith Howard and her young son visited the lighthouse from her home in Lakeport in August 1915, along with Edna, who was still teaching in Gilroy, and Bessie, now teaching in Avila.

That same year, Bessie developed heart trouble. However, the paper noted in October 1915 that she was improving and planned to visit her sisters Edna in San Jose and Elsie in Lakeport as soon as she was able.

In November 1915, Smith traveled to San Francisco to take temporary charge of the lighthouse exhibit at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Bessie accompanied her father as far as San Jose so she could stay with Edna to recuperate.

In March 1916, Smith took a trip to San Jose to visit the still-ailing Bessie. When he returned, he reported she was much improved but would continue to stay up north.

Bessie Smith did not get better, contrary to her father’s belief when he saw her in March. She was moved from her sister’s home to San Jose’s Garden City Sanitarium, where she died on September 4, 1916. She was thirty years old.

At some point in 1917, if not earlier, Smith’s two assistant keepers appear to have turned against him. Things came to a head early the following year. In a letter dated January 2, 1918, former second assistant Wheeler Greene filed charges against Smith.

While the specific allegations Greene made are unknown, a report made by Silva gave evidence that Smith had, on numerous occasions, oppressed the assistant keepers by enforcing petty rules and regulations and, Rhodes wrote, “by actions which placed your own personal wishes and convenience ahead of the interests of the Government in the conduct of your station.” Silva told Rhodes that on December 31, 1917, when he was going on watch, Smith spoke to him as if he were “not a human being,” said he would not be friends with Silva, that he had gotten rid of one man (presumably Greene) and intended to “finish it up.”

In a letter written January 10, 1918, Rhodes gave Smith a stern warning, hinting at dismissal if the Keeper failed to stop treating his assistants the way he had been and calling his attention to lighthouse service instructions that “superiors of every grade are forbidden to oppress those under them by tyrannical conduct or by abusive language.”

In response, on January 12, Smith submitted his resignation to take effect, he wrote, March 31, 1918. Then, on February 2, having had second thoughts, Smith requested his resignation be withdrawn. The lighthouse service agreed.

By 1920, Smith’s health was declining. In May, due to poor health, he applied for a three-month leave. In a June 9, 1920, letter to Smith, Rhodes approved his request and directed him to turn the station and all government property over to Silva, who was put in charge during Smith’s absence.

Unfortunately, Smith’s health did not improve. During his leave, he submitted his resignation. This time he did not change his mind. George Watters arrived in July 1920 to take over the Keeper post. Smith’s lighthouse service career was over.

Smith’s service at Point San Luis is left to the reader to judge. Did Smith deserve his commendations, or did they come at the expense of harshly treating his assistants? Did Silva and Greene give fair testimony, or did his two assistants turn against him for reasons we will never know?

A version of this story appeared in the November–December 2017 edition of Lighthouse Digest Magazine.