by Kathy Mastako, Member, Board of Directors, Point San Luis Lighthouse Keepers

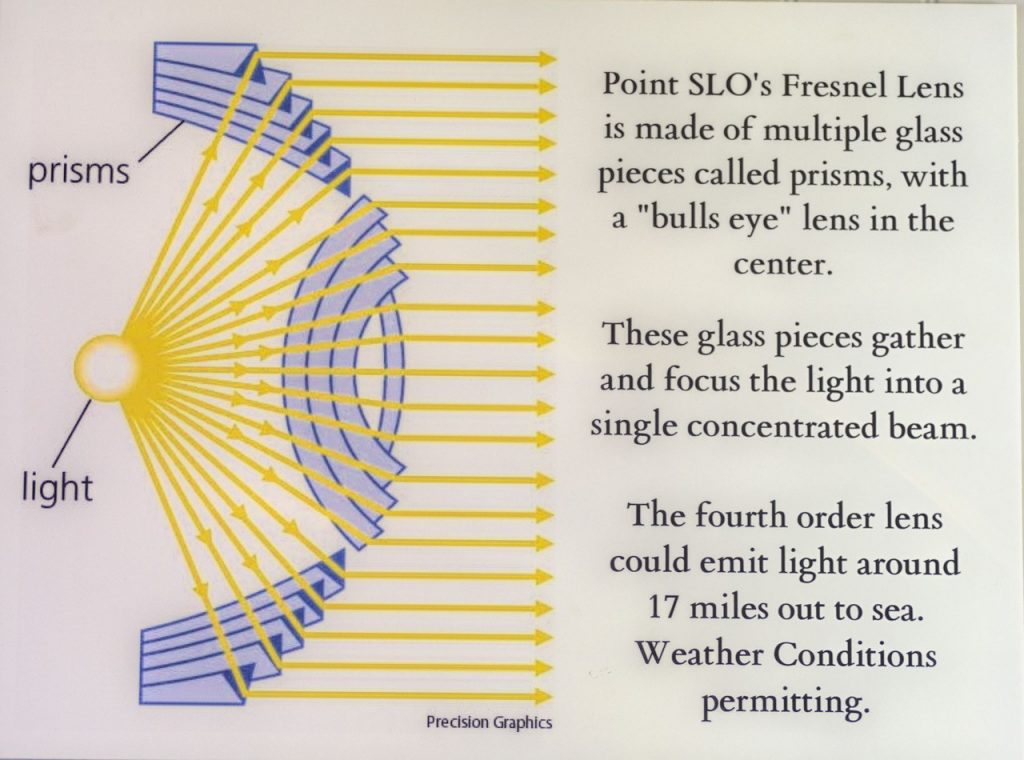

When the fourth-order Fresnel lens purchased for Point San Luis was installed in 1890, it alternated between red and white flashes every half-minute. The color was produced by ruby glass screens attached to every other one of the lens’s ten flash panels.

The light had been a long time coming. As far back as 1880—perhaps even before—shipping companies had been clamoring for a light, either on Whaler’s Island or on the mainland. Agents for the Pacific Coast Steamship Company petitioned Congress in 1881, arguing that a light would not only benefit vessels entering San Luis Bay but also ships passing up and down the coast. The steamship company pointed to the unfortunate absence of any light between Piedras Blancas and Point Conception, “leaving a space of about forty miles which is not illuminated by the rays of either of these lights.” The company even went so far as to install its own private light and employ a man to tend it. How long this arrangement lasted is unknown.

At about the same time the steamship company was writing to Congress, the Queen of the Pacific was being built in Philadelphia:

“There is now on the stocks and nearly completed at the yard of Cramp and Sons…a splendid iron steamship for the Pacific Coast Steamship Company, for service on the [Pacific] coast…she will be the strongest and finest specimen of marine architecture under the American flag…”

—San Luis Obispo Tribune, November 12, 1881

In 1882, while waiting to see if Congress would appropriate funds for a navigation aid for San Luis Bay, the lighthouse board considered whether Whaler’s Island or the mainland would be a more suitable site. Discussion also started about what type of light would be best. An 1880 lighthouse board report had recommended a third-order lens with a fixed white flash. In 1884, however, the twelfth district lighthouse engineer had other thoughts and wrote to the board’s chairman:

As the steamers passing are always bound into the Port Harford roadstead, and as the coast both north and south is free from outlying dangers, the light does not need to be visible from any considerable distance, and I am now of the opinion that a fourth-order [lens] would suffice. As Piedras Blancas to the north is fixed white varied by white flashes, and Point Conception to the south is flashing white every thirty seconds, it would seem desirable to introduce red at San Luis as a better distinction.

The engineer noted that the lighthouse board’s supply depot on Yerba Buena Island, Ca. had a fourth-order revolving lens in stock:

…sent out here as a temporary substitute for Point Conception during the changes at that station. It is arranged for flashes at intervals of thirty seconds; by making each alternative one red, the requirement of the new station would seem to be fulfilled, and an important saving effected.

Absent any money to establish a light, the lighthouse board nevertheless continued to discuss its location, going back and forth about whether Whaler’s Island or “San Luis head” would be the better site and whether it would be better to put a fog signal on the island and a light on the mainland. The federal government, by executive action, had acquired Whaler’s Island and planned to purchase thirty acres on the mainland from John Harford.

In 1887, the matter was settled. The lighthouse board determined both a fog signal and a light should be placed on the mainland. Congress appropriated fifty thousand dollars for the project. The board agreed the light should flash red and white alternately at thirty-second intervals. The twelfth district lighthouse inspector told the board, once again, “a fourth-order lens and revolving apparatus flashing white every thirty seconds is now stored in the depot at Yerba Buena and could be inexpensively modified here to serve the purpose.”

However, before the lighthouse board decided to give the go-ahead to build a light station, a near-catastrophe occurred. On April 30, 1888, at 8 a.m., the Queen of the Pacific groped her way into Port Harford, having sprung a leak:

Before dawn, the steamer listed so badly that it was difficult to walk the decks, and when the port was reached, the railing on the upper deck was submerged, and when within about thirty yards of the wharf, the steamer settled to the bottom in about twenty feet of water. Some two hundred and forty passengers were aboard, and all reached shore in safety. During the voyage, the ocean was unusually smooth, which accounts for the happy termination of the affair. Had a rough sea prevailed, it is quite probable there would have been considerable loss of life.

—San Francisco Bulletin, April 30, 1888.

The sinking of the Queen seemed to fast-track, putting a fog signal and light at Point San Luis. The following month, the government acquired title to Harford’s thirty acres. The twelfth district engineer began drawing up plans. In 1899, the engineer solicited bids to build the light station and awarded the contract to George Kenney of Santa Barbara.

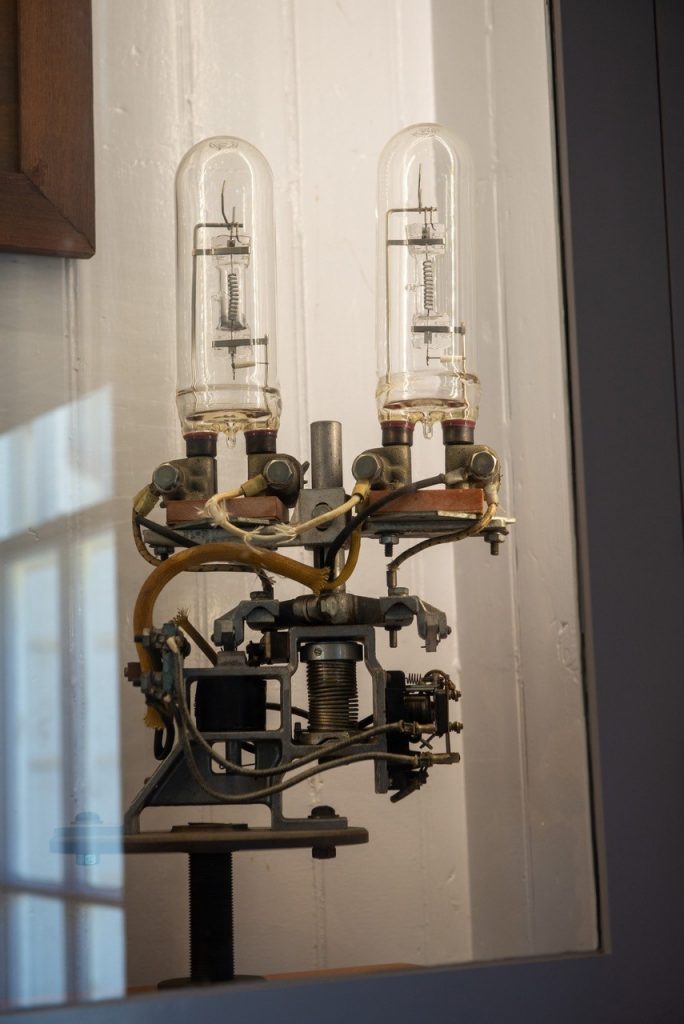

In November 1899, the lighthouse board asked the engineer in charge of the supply depot on Staten Island, N.Y., to fit up a fourth-order lens in its inventory with ruby glass panels to make it flash both red and white. Perhaps the lens once in stock at Yerba Buena Island had been deployed somewhere else. The lens at Staten Island was made by Sautter Lemonnier in France in 1878 and was numbered 325. Its various pieces—lens, clock, flash panels, pedestal, service table, lamps, and fitments—were contained in five cases, numbered 991 through 995. The cases were shipped from New York to San Francisco, then to Point San Luis.

On June 3, 1890, the lighthouse board issued a Notice to Mariners:

Notice is hereby given that, on or about June 30, 1890, a light of the fourth order, showing red and white flashes alternately, with intervals of thirty seconds between flashes, will be exhibited from the structure recently erected at San Luis Obispo.

Almost from the start, there was concern about how far out to sea the red flashes could be seen. The red glass was too dense and not the proper shade. The suggested remedy, to insert panels of clearer red glass like the panels in use at Point Sur, could not be achieved. Better quality red glass could not be found.

Finally, in 1912—twenty-two years after the light was first lit—the Bureau of Lighthouses approved changing the “characteristic,” or flash pattern, of the light by removing the red glass screens. About September 10, 1912, its characteristic was changed to flashing white only, every twenty seconds.

In November 1915, Point San Luis Keeper William Smith traveled to San Francisco to take charge of the lighthouse exhibit at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition for three weeks.

Keepers chosen to staff the lighthouse exhibit were selected by the Pacific Coast’s lighthouse district inspectors as a reward for faithful service. The keeper’s job was to care for and explain the equipment on display.

Smith returned to Point San Luis in early December. On December 2, 1915, the acting commissioner of lighthouses wrote to the third district inspector in charge of the Staten Island supply depot, suggesting the eighteenth (formerly twelfth) district inspector could use the modern fourth-order lens in the lighthouse exhibit if it was not intended for use after the Exposition ended. The eighteenth district inspector wanted it for Point San Luis “where a stronger light is required.”

Perhaps Smith had the ear of the eighteenth district inspector while he was tending the lighthouse exhibit and pressed his case for needing a better lens, suggesting that Point San Luis should be given the modern lens after the Exposition was over.

The third district inspector replied right away, stating that the new lens had been purchased specifically for the Exposition, and there was no requisition the supply depot had received that would require its use elsewhere. “If the Bureau does not desire to keep the exhibit intact, this office sees no objection to the lens, clock, and pedestal being used by the 18th inspector.”

The offer, however, was not without strings. The eighteenth district inspector could have the apparatus, but he would have to pay for it. This apparently was a deal-breaker. Point San Luis never got the Exposition lens; the original fourth-order lens, the one manufactured in France in 1878, remained in the lighthouse tower.

The lens flashed its welcoming beam from 1890 until 1974 when an automated beacon was installed on the lighthouse grounds. In 1976, the lens was moved for safekeeping to the museum in San Luis Obispo’s historic Carnegie library. In 1999, it was moved again, this time to the nearby San Luis Obispo city-county library. Finally, in 2010, it was returned to Point San Luis and installed in a special room inside the fog signal building, where docents explain its history and operation to guests taking lighthouse tours.

Those interested in viewing the lens can do so as part of a docent-led virtual tour. Public tours run Wednesdays at 2 p.m. (my805ix.com); private tours can be arranged (sanluislighthouse@gmail.com).