Not all memories are happy ones

Coast Guard officer Richard N. “Dick” Teeter came to the Point San Luis light station in January 1948 from the New Dungeness Lighthouse in Washington. He replaced another officer, Charles A. Garber, who had taken over as Keeper after Bob Moorefield retired. Garber, age twenty-nine but already with twelve years of Coast Guard service under his belt, left for the Point Arena lighthouse with his wife and four-year-old daughter in February 1948, leaving thirty-year-old Teeter as officer-in-charge.

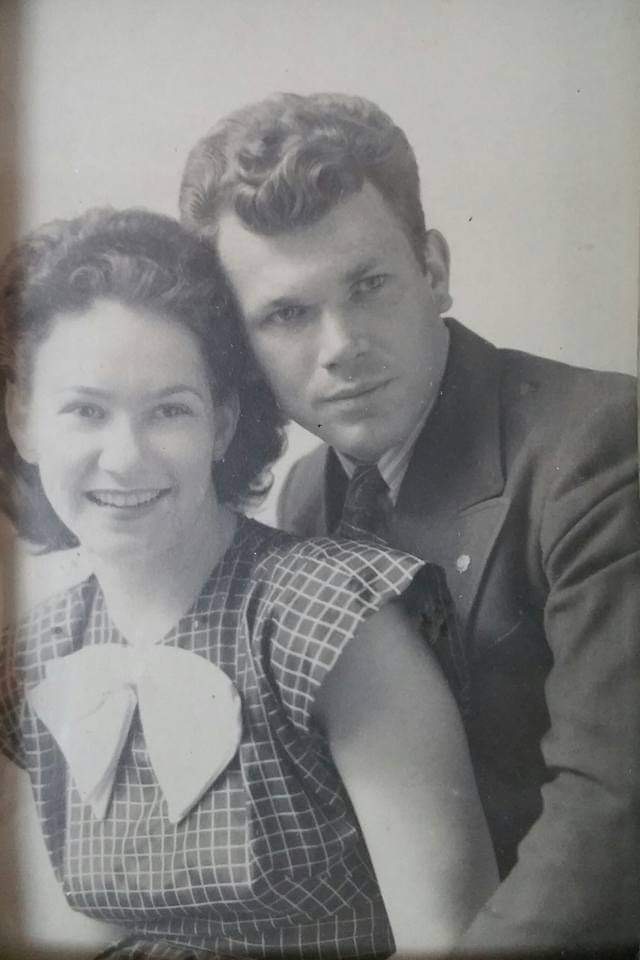

Teeter lived at Point San Luis with his wife Katherine, his stepson John, and his daughter Linda who was born in San Luis Obispo’s Mountain View hospital while they were stationed there.

John was five years old when the family arrived. He has fond memories of Point San Luis and Avila, or at least he did until Sept. 25, 1949.

John recalled that his family lived in the Keeper’s dwelling (the Teeters were probably the last family to live in that dwelling). Once the cinderblock duplex was finished—the accommodations built by the Coast Guard in 1948—the family moved into the right side of the duplex. The new duplex had up-date-date appliances, with an electric stove and heating.

John recalled that the Keeper’s dwelling had a door on the left side that opened to the cellar. Coal delivered by the Coast Guard buoy tender every couple of months would be shoveled through that door and stored in the cellar for use in the coal-burning stove and fireplaces. His mother was thrilled to move to the cinderblock duplex so she would not have to deal with coal any longer.

Sometimes John would accompany his stepdad up the narrow stairs of the lighthouse tower to tend the light. He recalled that the lens was kept meticulously clean and that he was told never to touch the glass or the brass. One time, though, he was allowed to clean the brass under very close supervision. John was also allowed to go outside on the gallery deck that surrounded the light while he was with his stepdad. “You could see forever up there.”

John and a few other Coast Guard children would walk back and forth to the two-room Avila schoolhouse each day, unaccompanied by an adult. He remembered being warned not to move off the trail:

First on our minds was, can we get a ride to school once we get down the hill to the port pier. Often the trip was muddy, damp, and cold. If we were lucky, we could get a ride from fishermen coming and going on the dirt road. One time, after a rain, I got to school so muddy, the teacher had to take me to her house to clean up. I hated it when it was warm and sunny. There was a part of the trail where large black and white king snakes and gopher snakes would lay across the trail sunning themselves.

Dick was very strict with me. I had a fifteen-minute arrival window when walking back home from school. I know now that was because there would be an alert to look for me and others if we were late.

The trail often needed maintenance work, so Dick would send someone to make the repairs. They even hung guide wires in certain gullies for us to hold onto as we crossed over. Once we got to the port pier, as it was sometimes called, we tried our best to hitchhike the rest of the way to school with the fishermen who were coming and going.

Sometimes, John recalled, he and his Coast Guard classmates would be transported to the Avila pier by boat instead of walking the trail to school. “That was always fun for me.”

The Coast Guard was well-liked in Avila, John remembered, and his stepdad had a lot of friends both in commercial fishing and in charter boats. John loved being out on the piers watching the fishing boats come in:

Avila was a wonderful hamlet. There was an old wooden water wheel up a ways on the creek. We used to play there. At the time, Avila had the reputation of being a very safe surf beach. So, for the most part, we ran amuck unsupervised.

One of the things we kids figured out was that, when there were a lot of tourists in Avila during the summer months, we could take sand strainers and go under the pier and find coins that were dropped by passersby. A penny or a nickel was big money in those days.

I used to make pocket change by pushing a railed cart out to the end of the pier when the charter boats came in. They would pile their tackle or fish on the cart, and I would push it back to the road.

Dick Teeter had been at Point San Luis about twenty-one months when, at 5:50 p.m. on Sept. 25, 1949, he, fellow Coast Guardsman Harry Alexander, and Adam Stewart Douglas, a civilian, decided to take the station’s weapons carrier to Pecho Creek to inspect the water pipeline, which had apparently become clogged. (The creek, along with rainfall, supplied water to the light station.) Teeter was driving when the vehicle plunged off the “Marre road” near Avila and down a sixty-foot embankment. Teeter was crushed by the vehicle, killed instantly; Douglas was severely wounded. Alexander, who escaped with minor injuries, walked four miles over the hills back to the station, arriving at about 8:30 p.m. to report the accident. On Oct. 7, Douglas died of his injuries.

What Douglas was doing at the station and why he accompanied Teeter and Alexander in the weapons carrier to inspect the pipeline is unknown. He must have been friends with the station’s personnel; two Guardsmen—Harry Alexander and Kenneth Chapman—were pallbearers at Douglas’s funeral.

Their lives turned upside-down, Teeter’s family left the station shortly after the accident, moving to Avila. John was sent to boarding school. Eventually, John’s mother remarried. His new stepfather was one of the fishermen—an abalone diver—who occasionally gave him a ride to school.